Two years before the centenary of the 1904 Welsh revival, the National Screen and Sound Archive of Wales (based at The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth) received a phonographic cylinder that claimed to be a recording of the revival’s charismatic figurehead, Evan Roberts (1878–1951).

It offered the tantalizing possibility of providing a more rounded profile of the man. We knew what he looked like from photographs, and we knew his ideas from what he wrote and was reported as having said. But we didn’t know what he sounded like – his vocal signature: the tone and character of the voice that had captivated thousands of people during the religious awakening. But this audible relic could no more surrender its content than a shattered mirror return a faithful image.

The cylinder had been broken into eleven extant pieces. After a painstaking repair by Michael Khanchalian, an American dentist and wax cylinder restorer, it was capable of being played once again. Against the insistent noise of surface clicks and crackles, and the rhythm of the stylus as it ploughs through the spinning furrows, the febrile voices of Roberts and a small choir of male singers are discernible. A digital transfer of the recording was prepared by a sound studio in Los Angeles, California and the British Library, London. This version forms the basis of my suite of works.

On hearing about the repaired wax cylinder, two questions occurred to me: What might the cylinder have sounded like if it could have been played in its fractured condition? And in how many different ways could the cylinder have been reassembled? In the material realm, both interrogations are redundant: one cannot play a broken wax cylinder, and its parts can fit back together in only one way. Nevertheless, these questions ignited my desire to engage with the artefact in its state of ruin. I wanted to create new unities out of the cylinder’s pre-glued disorder that would explore the audio aesthetic and the artefact’s openness to possibilities. In the digital realm this is entirely feasible. The engagement has liberated ideas and significance that are not evident when the recording is heard intact. In line with my principle of practice when making visual images, the manipulation of the source material is determined, as far as possible, by its intrinsic characteristics and extrinsic circumstances. Accordingly, the processes and concepts that inform my intrusion into the cylinder arise solely from the content and nature of the medium, and the context and culture of its creation.

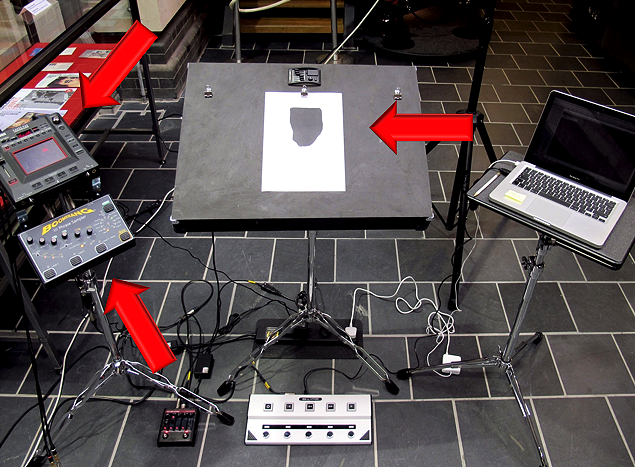

Each sound piece begins visually, with the shape of one of the 11 fragments. The outline of a fragment is traced manually on an electro-acoustic drawing board – a bespoke box-chamber containing a microphone. The sound of the drawing is recorded and looped and, finally, modified tonally through a filter to give it the sonic characteristics of a wax cylinder recording. The cyclical nature of the sound-drawing’s reiteration mimics the revolution of the wax cylinder. The other samples used in the compositions comprise sections edited and dislocated from the digital version of cylinder’s audio content. They include surface noise, and single words, phrases, and sentences taken from Roberts’ homily and the choir’s singing. The sound-art works further extend the process by which Roberts’ voice has been subjected to audio recording and playback technologies. The audio material is re-recorded, reordered, recomposed, rearticulated, equalized, sampled, and transcribed. In this way, the cylinder is fractured once again. The voice extracts are variously repeated, reversed, slowed down, speeded up, cut up and spliced, overlaid, and filtered. The duration of each piece is within the maximum time-span of an early-twentieth century wax cylinder (approximately 4 minutes).

A wax cylinder is hollow (open at both ends), a conduit rather than a container, through which past and present, reality and its revisions, course and merge. Accordingly, the suite of works is a contemporary and imaginative response to historical data – a series of conjectural, counterfactual reconstructions or fictive extensions of the sonically encoded fact. The sound-art works adapt the audible content, the characteristics of the recording process, and the physical condition of the cylinder as a means of evoking and conflating, acoustically, aspects of Roberts’ biography and the revival’s history – to develop a series of meditations upon the source that engage both intellect and feeling. In so doing, the works summon associated experiences, events, emotions, critiques, and significances that are otherwise inaccessible to, or inexpressible through, visual and textual documentation.

R R B V E Ǝ T N Ƨ O A is the first CD release in The Aural Bible series. The series deals with the Judaeo-Christian scriptures as the written, spoken, and heard word. It explores the cultural articulations and adaptations of the Bible within the Protestant tradition. The works on the album embark upon a critical, responsive, and interpretive intervention with aspects of its sound culture. The websites that accompany the series’ albums are dynamic. Material will be added, and sub-sections fleshed-out, as opportunities for the work to be presented, discussed, reviewed, and broadcast, present themselves.

This website includes descriptive and background material for each of the individual compositions comprising the sound suite. It does not seek to fully explain their nature but, rather, to provide sufficient guidance to enable the listener to appreciate how the works are constructed and informed by the themes, history, and texts to which they respond.

John Harvey

March 2014

Throughout the site, text is red indicates a hyperlink.

R R B V E Ǝ T N Ƨ O A is the first CD release in The Aural Bible series. The series deals with the Judaeo-Christian scriptures as the written, spoken, and heard word. It explores the cultural articulations and adaptations of the Bible within the Protestant tradition. The works on the album embark upon a critical, responsive, and interpretive intervention with aspects of its sound culture. The websites that accompany the series’ albums are dynamic. Material will be added, and sub-sections fleshed-out, as opportunities for the work to be presented, discussed, reviewed, and broadcast, present themselves.

This website includes descriptive and background material for each of the individual compositions comprising the sound suite. It does not seek to fully explain their nature but, rather, to provide sufficient guidance to enable the listener to appreciate how the works are constructed and informed by the themes, history, and texts to which they respond.

John Harvey

March 2014

Throughout the site, text is red indicates a hyperlink.